Blog 2: Graphic Novels Are Not Literature

Lit•er•a•ture: noun

1. writings in which expression and form, in

connection with ideas of permanent and universal interest, are characteristic

or essential features, as poetry, novels, history, biography, and essays.

—www.dictionary.com

Before we can discuss what Graphic Textbooks are we need to

understand their origin, which means we have to understand where the term “Graphic Novel” came from.

Originally conceived as a term that would define longer works of

sequentially illustrated stories containing mature themes, graphic novel

has become an umbrella phrase, a marketing tool for almost any work told

through the use of pictures. Simply put, the term graphic novel has devolved

to mean any illustrated story. Yet, that really is

too broad of a description to have any well-defined meaning.

If we conclude that a graphic novel must include text (words),

then how do we categorize Shaun Tan’s (1974–) The Arrival (2006)? If we maintain that the

artwork can only be sequential, then where do we place Jim Steranko’s (1938–) Chandler: Red Tide (1976)? If we insist that the

story consists of only one narrative then what is Will Eisner’s (1917–2005) A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories

(1978)? And if we demand that a graphic novel must be exclusively original and

not one that was initially serialized in a magazine, then should we not exclude

Art Spiegelman’s (1948–) Pulitzer

Prize-winning Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (1986 & 1991) from our list?

If we conclude that a graphic novel must include text (words),

then how do we categorize Shaun Tan’s (1974–) The Arrival (2006)? If we maintain that the

artwork can only be sequential, then where do we place Jim Steranko’s (1938–) Chandler: Red Tide (1976)? If we insist that the

story consists of only one narrative then what is Will Eisner’s (1917–2005) A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories

(1978)? And if we demand that a graphic novel must be exclusively original and

not one that was initially serialized in a magazine, then should we not exclude

Art Spiegelman’s (1948–) Pulitzer

Prize-winning Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (1986 & 1991) from our list?

These questions exist because of our common need to categorize

everything, because of the physical and financial limitations of printing and

binding, and because of Library Science’s requirement to catalog books into an

antiquated classification system. In truth, the academic discourse on graphic

novels, which has been almost wholly literary, has been viewed from a skewed

perspective.

Graphic novels were never literature’s bastard children, but that

is how they have been—and are still—perceived in some academic circles.

Comparable to film, graphic novels are a visual medium and apart from

literature in much the same way film is apart from literature. In truth, graphic novels

have never been a form of literature,

but they have always been an independent literate art form. To elucidate the dissimilarity, if one can

convert a published work into an audio book by reading just the text, without

losing any of the story’s nuances and meanings, then it is literature. This

test holds true for works of prose, poetry, and plays, but not for graphic

novels or film because so much of the story is conveyed visually.

This does not mean that graphic novels should no longer be read in

literature or other classes because the needs of the lesson outweighs the

format of the pedagogical vehicle; however, it does illustrate society’s

persistent problem with accepting graphic novels because of this

miss-association. Comic books became

trapped in a format and vernacular that has biased the public’s perception

since their inception. However, if we look at the Storytelling Family Tree we

see that pictoglyphs, petroglyphs, oral tradition, literature, film, and graphic

novels are all simply narrative vehicles growing out of the same trunk. Contemporary

Graphic Narratives [comic books,

graphic novels, comic strips, children’s picture books, certain forms of

illustrated books such as Dinotopia (1992)

by James Gurney (1958–)] grew apart from their cousins to form their own branch of

the Storytelling Family Tree. Because of their

visuality, the questions surrounding graphic novels should never have been:

“Are they, or are they not literature?” The questions should have focused on

“How can we cultivate the graphic novel format in order to tell better

stories?” By asking these types of questions, by “troubling the binary” as it

were, we acknowledge that graphic novels are a distinctive medium—a distinctive art form—set apart from both literature and film.

Unfortunately, removing graphic novels from the literary tradition

is problematic because there is no viable way to adequately market them to

academicians other than book review publications such as Booklist, Publisher’s Weekly,

and Library Journal to name a few.

Removing them from the literary tradition would also negate the literary awards

they have already received, and make them ineligible for future awards. Yet,

there is already a double standard at work here. While graphic novels have been

considered for literary awards, such as a Special Pulitzer Prize and the World

Fantasy Award, there has never been a text-only book that was considered for

any of the graphic novel honors such as the Eisner Award or the Harvey Award.

It is, however, vitally important to separate graphic narratives from

literature because the comparison stifles growth and creativity. By

understanding that they are an art form independent from literature, graphic

narratives no longer need to fit into the narrow confines of form and format

that has been imposed upon them. It means that they can freely evolve as the creators

envision them through a process of artistic growth.

The Origin of the Term, and the First Modern Day

Graphic Novel

Contrary to popular belief, Will Eisner’s A Contract with God

and Other Tenement Stories was not the first time the term graphic novel was used, nor is it the

first modern graphic novel. The first printed usage of the term appeared in

Richard Kyle’s November 1964 newsletter published in CAPA-ALPHA #2

(Fingeroth, 2008, 3). Previous derivations on the theme such as “Picture

Novel,” and “Picto-Fiction” appeared on paperbacks and magazines in the 1950s.

The first Picture Novel, and, arguably, America’s first graphic novel was It

Rhymes with Lust (1950). The digest-sized, 128-page book was produced by

St. John Publications (1947–1958), which was founded by Archer St. John (1904–1955). It Rhymes With Lust was written by Arnold

Drake (1924–2007) and Leslie Waller (1923–2007) under the pseudonym “Arnold Waller,” drawn by Matt

Baker (1921–1959), and inked by Ray Osrin

(1928–2001).

Baker was one of the medium’s first African American artists, and one of the

forerunners of the “Good Girl Art” movement, working on titles such as Phantom

Lady, and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. Inspired by film noir, It

Rhymes With Lust was a character-oriented romance/detective story. Though

the story is typical of genre films of its time, It Rhymes With Lust

also contained an underlying social commentary about greed, graft, and worker’s

rights. St. John’s second graphic novel was The Case of the Winking Buddha

(1950), by novelist Manning Lee Stokes (1911–1976) and illustrator Charles Raab. Unfortunately, both of

these books failed financially, and the format was abandoned (Kitchen, 2011).

Though it may be considered a collection of short stories, Harvey

Kurtzman’s Jungle Book (1959) is the prototype for the graphic anthology

format. Jungle Book was written and illustrated by Harvey Kurtzman (1924–1993), who was the founding

editor of MAD (1952) magazine. Kurtzman was a highly influential

creative force in the comics industry, and helped shape much of America’s

popular culture during the 1950s (Wright, 2003). Jungle Book was a

commercial failure; however, it had a tremendous impact on the Underground

Comics artists of the 1960s (Kitchen, 2011).

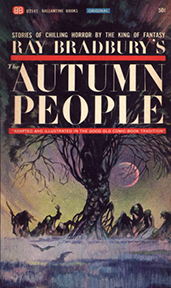

Another forgotten series of books from the mid-1960s, are the

Ballantine Books paperback reprints of Mad

magazine and the EC Comics line of early 1950s horror stories. Because

paperbacks were not sold with comic books they did not come under the scrutiny

of the Comics Code Authority and its restrictions. Among these titles were, Autumn People (1965) with stories by Ray

Bradbury (1920–) adapted

by Albert “Al” B. Feldstein (1925–), The Vault of Horror (1965), Tales From the Crypt (1964), Tales of The Incredible (1965), and Dracula (1966). While the other books

contained reprints, Dracula was an

all-new adaptation of “The great horror classic illustrated in comic book

form!” Produced by Russ Jones (1942–), the

text for Dracula was adapted by Otto

Oscar Binder (1911–1974) and Greg Tennis (Nom de plume for Johnny Craig [1926–2001]), illustrated by Alden “Al” McWilliams

(1916–1993), and contained an Introduction by Christopher Lee (1922–). Another, similar volume, albeit printed by Pyramid Books,

was Christopher Lee’s Treasury of

Terror: Great Picture Stories of Supernatural Horror (1966). As with Dracula, the Christopher Lee book was

produced by Russ Jones, but was an anthology of stories selected by Lee, and

adapted by various writers and artists. None of these books sold well enough to

warrant subsequent volumes; however, Dracula

was, historically, the third graphic novel (following It Rhymes With Lust,

and The Case of the Winking Buddha) and the Christopher Lee book

was the second anthology of original work following Jungle Book.

Another forgotten series of books from the mid-1960s, are the

Ballantine Books paperback reprints of Mad

magazine and the EC Comics line of early 1950s horror stories. Because

paperbacks were not sold with comic books they did not come under the scrutiny

of the Comics Code Authority and its restrictions. Among these titles were, Autumn People (1965) with stories by Ray

Bradbury (1920–) adapted

by Albert “Al” B. Feldstein (1925–), The Vault of Horror (1965), Tales From the Crypt (1964), Tales of The Incredible (1965), and Dracula (1966). While the other books

contained reprints, Dracula was an

all-new adaptation of “The great horror classic illustrated in comic book

form!” Produced by Russ Jones (1942–), the

text for Dracula was adapted by Otto

Oscar Binder (1911–1974) and Greg Tennis (Nom de plume for Johnny Craig [1926–2001]), illustrated by Alden “Al” McWilliams

(1916–1993), and contained an Introduction by Christopher Lee (1922–). Another, similar volume, albeit printed by Pyramid Books,

was Christopher Lee’s Treasury of

Terror: Great Picture Stories of Supernatural Horror (1966). As with Dracula, the Christopher Lee book was

produced by Russ Jones, but was an anthology of stories selected by Lee, and

adapted by various writers and artists. None of these books sold well enough to

warrant subsequent volumes; however, Dracula

was, historically, the third graphic novel (following It Rhymes With Lust,

and The Case of the Winking Buddha) and the Christopher Lee book

was the second anthology of original work following Jungle Book.

By the early 1970s, the term graphic

novel was part of the comics creator’s vernacular; however, it was not used

to describe America’s next attempt at a graphic novel, Blackmark (1971).

Blackmark was conceived by Gil Kane (aka Eli Katz 1926–2000), written by Archie Goodwin

(1937–1998) and illustrated by Kane over

uncredited pencil layouts drawn by Kurtzman (Kitchen, 2011). Published by

Bantam Books, Blackmark was a 119-page science fiction/sword and sorcery

heroic fantasy graphic novel printed in a traditional paperback format. While

conceived as the first in a sequence of ongoing graphic novels, sales of the

first volume were poor, which led to the cancellation of the series.

The first self-referential use of the term graphic novel appeared on the January 1976 publication Schlomo

Raven. Written by Byron Preiss (1953–2005) and illustrated by Tom Sutton (1937–2002), Schlomo Raven also contained an Introduction

by Kurtzman. Printed in large bold letters on the back cover of the

digest-sized paperback were the words “—VOLUME ONE OF AMERICA’S FIRST ADULT

GRAPHIC NOVEL REVUE!” Schlomo Raven was the first in Pyramid Books’ Fiction

Illustrated series aimed at a more mature audience. The series also

included: Starfawn (1976), by Byron Preiss

and Stephen Fabian (1930–); Chandler: Red

Tide, by Jim Steranko; and Son of Sherlock Holmes: The Woman in Red

(1977), by Bryon Preiss and Ralph Reese (1950? –). Even though Schlomo Raven was published twenty-one months

before A Contract with God, its place in graphic novel history has been

largely overlooked along with the other Fiction Illustrated volumes. In their

day, the odd format and sporadic paperback distribution made them curiosities

among comic fandom buyers who did not appreciate change (Steranko, 2010). When

combined with the fact that none of these volumes has ever been reprinted

(mainly due to legalities resulting from the death of Preiss), and that the

stories, except for Chandler, are only of cursory interest, it is not

surprising that they have been forgotten.

The first self-referential use of the term graphic novel appeared on the January 1976 publication Schlomo

Raven. Written by Byron Preiss (1953–2005) and illustrated by Tom Sutton (1937–2002), Schlomo Raven also contained an Introduction

by Kurtzman. Printed in large bold letters on the back cover of the

digest-sized paperback were the words “—VOLUME ONE OF AMERICA’S FIRST ADULT

GRAPHIC NOVEL REVUE!” Schlomo Raven was the first in Pyramid Books’ Fiction

Illustrated series aimed at a more mature audience. The series also

included: Starfawn (1976), by Byron Preiss

and Stephen Fabian (1930–); Chandler: Red

Tide, by Jim Steranko; and Son of Sherlock Holmes: The Woman in Red

(1977), by Bryon Preiss and Ralph Reese (1950? –). Even though Schlomo Raven was published twenty-one months

before A Contract with God, its place in graphic novel history has been

largely overlooked along with the other Fiction Illustrated volumes. In their

day, the odd format and sporadic paperback distribution made them curiosities

among comic fandom buyers who did not appreciate change (Steranko, 2010). When

combined with the fact that none of these volumes has ever been reprinted

(mainly due to legalities resulting from the death of Preiss), and that the

stories, except for Chandler, are only of cursory interest, it is not

surprising that they have been forgotten.

Other graphic novels soon followed, including: Robert Ervin Howard’s

(1906–1936) Bloodstar

(1976), adapted by illustrator Richard Corben (1940–); Beyond Time and Again: A Graphic Novel (1976), by

George Metzger (1939–); Sabre: Slow Fade of

an Endangered Species (1978), by writer Don McGregor (1945–) and artist Paul Gulacy (1953–); The Silver Surfer (1978), by Stan Lee (1922–) and Jack Kirby (1917–1994);

The First Kingdom (1978), by Jack Katz (1927–); Comanche Moon (1979), by Jaxon (Jack Jackson,

1941–2006); and Tantrum (1979), by

Jules Feiffer (1929–).

The critically acclaimed A Contract with God was the first

modern graphic novel to deal exclusively with the human condition. It

revolutionized the comics industry by becoming the first commercially

successful graphic novel (Kitchen, 2011). While some detractors claim that A

Contract with God is actually a collection of short stories, and not a

novel per se, the use of multiple stories with an underlying connective theme

is not without precedent, and is the basis for books such as Winesburg, Ohio

(1919) by Sherwood Anderson (1876–1941), and The Wild Palms [If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem]

(1939) by William Faulkner (1897–1962). Its

longevity and continued popularity speaks to its broad market appeal and

timeless stories. Additionally, its semi-autobiographical approach established

a standard by which all other slice-of-life graphic novels are compared. Even

though Eisner did not invent the term graphic novel, its use on the cover of A

Contract with God popularized it, and brought it into public forum

(Kitchen, 2011).

Topics for Discussion

1)

This is a bunch of hooey. Graphic novels are literature because…

2)

The public’s acceptance of graphic novels has increased over the past decade.

What factors would you attribute to that change?

3)

What is missing from this review of the literature?

This is a great article which has really helped me think about a project I'm putting together called Dawn of the Unread. I'm not trying to plug this on your comment stream, but mention it as this is a new genre/medium to me and your article was really helpful. I've chosen the graphic novel for my project because it opens up so many possibilities and can engage different readers on so many levels. Thanks

ReplyDelete